Performance as Activism and Utopia in the Americas

“Occupy the imagination, before someone else does” read the slogan of filmmaker Rodrigo Dorfman for his 2013 movie “Occupy the imagination: Tales of seduction and resistance.” The film took as a point of departure the book “How to Read Donald Duck”, that Rodrigo Dorfman’s father, Chilean author Ariel Dorfman wrote and published in 1971, under Allende’s government. The book, that Rodrigo calls “a manual to decolonize our imagination,” explored the racist, colonial, and imperialist subtext in Disney’s cartoons, and it was banned after the 1973 coup in Chile, Argentina and Uruguay, as well as in the U.S. The slogan “occupy” as a motto for resisting and challenging capitalism has been since its inception criticized by academics of color, most poignantly by Jessica Yee, for its lack of acknowledgment of colonialism, and of the fact that the land where anti-capitalist struggles are taking place are already “occupied” and in fact need to be decolonized.

The question of what does it mean to decolonize our imagination in the Americas? lingers in my mind and I find no easy answer. As a mestiza, I am a product of Spanish colonialism, and have no original authentic identity, culture or land to claim or come back to. And if our imaginations are colonized at such an early age through means like cartoons, how are our anti-capitalist and anti-neoliberal political projects and practices bound by our colonized imaginations? How can we desire utopia when we cannot imagine it? In contexts of state violence, how can we forge a sense of futurity that does not require completely renouncing the past? And how can we reconcile imagining our future without being asked to forget and stop grieving our dead? These are the broader questions that frame my interest in activism and performance.

Growing up I often came across this image created by the Uruguayan artist Torres García in 1943 called “Inverted Map of South America.”

The power of this image, of course, resides in the fact that it reminds us of the completely fictional status of maps (space doesn’t have a point of reference to decide which America is on “top” versus “bottom”), and the power they possess for construing and constructing world. Our maps, and the way we understand our place in the world, our “cartographies of the feasible” to use Jacques Ranciere’s concept, prefigure our political imaginations and thus, our political subjectivities, projects, and practices. For example, when we prefigure solidarity across the Americas starting out by the modern Eurocentric map of the world, our subjectivities and practices will be bound by a north-south hierarchy that assumes the cultural superiority of the north, and an implicit logic of “who helps who”. Physical and symbolic national borders shape political projects and define political subjects, as we take nations as points of reference, instead of, for instance, looking at the commonalities of oppressed groups across national borders, and across the Americas or Abya Yala.

Transnational feminist scholars and activists have been doing exactly this through establishing connections between the precarious conditions for labor of women across the world established by Free Trade Agreements, migration patterns triggered by the imperialist policies of the IMF and the World Bank, and the progressive impoverishment and displacement of Indigenous and peasant communities across the Americas.

Transnational feminist scholars and activists have been doing exactly this through establishing connections between the precarious conditions for labor of women across the world established by Free Trade Agreements, migration patterns triggered by the imperialist policies of the IMF and the World Bank, and the progressive impoverishment and displacement of Indigenous and peasant communities across the Americas.

I am interested in exploring practices that aim to decolonize our imagination and foster a sense of utopia in a twofold sense: One, that they contribute to unsettle our sense of space expressed in deeply embedded maps of the world with its tops and bottoms, as well as with national borders. Two, that they disrupt what I call “traumatic temporalities,” a concept I used in my research on the Chilean post-dictatorship, to describe a sense of futurity linked only to forgetting the past and to accepting neoliberal policies. I also apply this term here to the Eurocentric timeline of modernity and progress that defines time as linear, with the racialized past behind us and the (white) future ahead. I will discuss in this lecture, how this model of temporality proves politically disempowering, as it urges oppressed groups of people, whose lives are still shaped by colonialism and state terror, to “move forward,” “get over the past”, or to assimilate. I ask if performance as an activist practice can disrupt this common sense about space and time to enable political imaginations and subjectivities that foster a sense of futurity and utopia in oppressed communities, across Abya Yala or the Americas. I do so from the perspective of a Latin American middle-class cisgender woman, with a hybrid/mestizo identity living in Canada. As Chilean citizen and an immigrant to Canada, I also acknowledge my complicated position within ongoing state colonialism (both in Chile and Canada) and processes of gentrification and reproduction of poverty in Saskatoon.

This lecture is meant to open a larger and ongoing dialogue to explore the lines of convergence and also of difference between several forms of performance in the context of activism in Latin America and of Indigenous and social justice activism in Canada. I ultimately seek to explore the commonalities and differences of these contexts to reflect on the conditions for building anti-colonial and anti-neoliberal solidarity across Abya Yala/Americas. Like Harsha Walia has suggested, “any serious social or environmental justice movement (and I include feminism here) must necessarily include non-native solidarity in the fight against colonization.” I want to clarify that I do not wish to speak “for” Indigenous scholars and activists here, and that my ground of expertise is not Indigenous Studies. I am rather looking to create a dialogue with Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars and activists on issues of cultural memory and political agency, and to reflect on how performance offers spaces that can be rehumanizing, healing, where collective subjectivities can be forged, and where audiences are interpellated by becoming witness of other's suffering.

My interest has never been particularly in performance art carried out in venues and institutional spaces sanctioned for artistic purposes, as much as in the use of “performance tactics” within the context activism of diverse social justice movements in urban settings, they are generally carried out in the streets of a city’s downtown, or a commercial centre, where it causes disruption to the normal flow of everyday life. I use Diana Taylor’s definition of performance as an embodied practice that transmits cultural memory and identity, and that can articulate what cannot be wholly conveyed by text, narrative, or discourse. Taylor, who studied the activism of the Madres de Plaza Mayo in relation to trauma and state terror during the “Dirty War” in Argentina, argues that the relevance of performance lies in its possibility for cultural agency, whereby individuals and collectives can become protagonists and politicized subjects of their own social drama.

Her analysis underlines that the relevance of performance lies in the transmission of cultural memories in contexts of trauma, where text and discourse cannot fully invoke the traumatic experiences, so that a different form of telling is required. Taylor also considers how Spanish colonization imposed the written word as the only valid means of transmitting knowledge, suppressing a long pre-colombine tradition of orality, ritual and ceremony. In my own research on the use of performance by queer and feminist activists in Chile, I argued that activist performance is a practice that invokes cultural memories of our recent past (Salvador Allende, Che Guevara) as a critique of the present, while creating utopian images for an alternative present and future.

Her analysis underlines that the relevance of performance lies in the transmission of cultural memories in contexts of trauma, where text and discourse cannot fully invoke the traumatic experiences, so that a different form of telling is required. Taylor also considers how Spanish colonization imposed the written word as the only valid means of transmitting knowledge, suppressing a long pre-colombine tradition of orality, ritual and ceremony. In my own research on the use of performance by queer and feminist activists in Chile, I argued that activist performance is a practice that invokes cultural memories of our recent past (Salvador Allende, Che Guevara) as a critique of the present, while creating utopian images for an alternative present and future.

I argued that these performances can be viewed as a contribution to the (re)articulation of political imaginations (utilizing the street as a public space for the practice of democracy) and subjectivities (putting forward the body both as a cultural construct, as a fiction, and as a site of political agency and power). I identified a utopian desire in the cases of activist performance I studied as they stretched their audiences political imaginations in the context of extremely constraining cultural coordinates. They do so by bringing into the scene affective connections to the past or “hauntologies,” based on the rejection of the dominant timeline of transition/ reconciliation/ post-dictatorship, a version of temporality that implies linear progress and evolution. At the same time, the cases of activist performance I studied defy the binary public/private space by pointing at the overlapping of public and private forms of violence. I will then look at these cases in Chile in relation to the uses of performance in activist contexts in Canada by exploring the themes of traumatic temporalities and public grieving, and trauma, performance, and the body.

Traumatic Temporalities, Public Grieving and “Hauntologies”

Early in the Chilean transition to democracy, it became apparent how cultural memory was a site of permanent contestation, and that the performativity of the past—the ability of the past to "do" things in the present—made memory and memorialization, and more broadly, the problem of temporality key for the articulation of political subjects in the present. For example, both the triumphalist discourses of the right and the defeatist/apologetic discourses of the left seemed to be done with the past, foreclosing any substantial discussion on the model of society and economy that was secured under Pinochet first and under the Concertación coalition later. Throughout the 1990s and onwards, the undeniable "reality" of capitalism, the market, and neoliberalism were presented as the only possible reality, making it imperative to adopt a pragmatic approach to political practice. From this perspective looking at the past is damaging for national reconciliation, unity and progress, as it puts a finger in the wound. The past is deemed conflictive, “political,” and divisive; thus, it needs to be forgotten and overcome. Traumatic temporalities can apply also to the colonizing of our sense of futurity. All across the Americas/Abya Yala, Indigenous cultures, languages, and systems of knowledge were turned into “museum cultures” by colonialism, associated to the fixed past, and presented as barbaric and backwards, while the future became associated with the expansion of European language and culture, of urban centres, capitalism, extractivism, and racial and cultural assimilation. Indigenous peoples and culture are deemed to disappear under this timeline that “naturally” tends to progress and betterment.

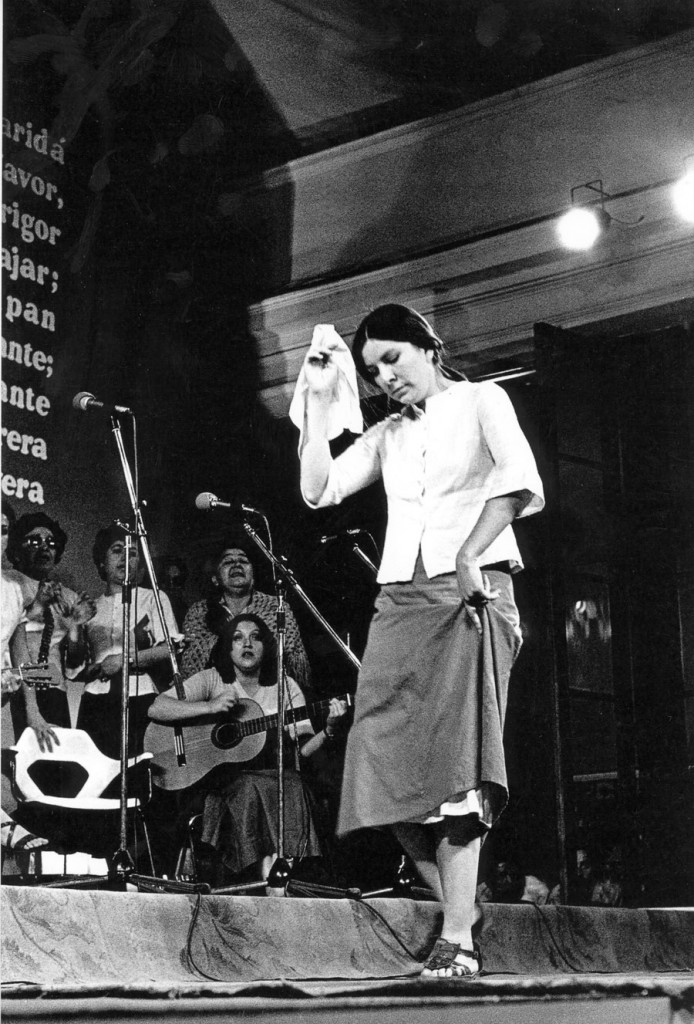

Under the repressive conditions of military dictatorships, protest tactics in the streets through the 1980s, particularly by human rights and feminist activists across Latin America, were profoundly impacted by the gendered performance tactics of the human rights activist group Madres of Plaza Mayo, in Argentina, after they inaugurated "public grieving and public suffering as political praxis" in the seventies and eighties (Bergman and Szurmuk 391). In response to the state violence of military dictatorships, both the Argentine Madres and the Chilean Agrupación de Familiares de Detenidos Desaparecidos, for decades, have been “performing public grieving” and regularly marking the presence of the disappeared in the streets through pictures, cut out bodily shapes, our through the cueca sola, in which the women (widows, daughters, mothers) literally dance with their disappeared relatives and loved ones.

The Madres performed motherhood as a way to avoid repression of political practice, and invoked the moral superiority of mothers that was part of the military ideology. While one could see these performances as marking the absence of the bodies of the victims, I consider whether they are indeed marking their insistent presence.

The Madres performed motherhood as a way to avoid repression of political practice, and invoked the moral superiority of mothers that was part of the military ideology. While one could see these performances as marking the absence of the bodies of the victims, I consider whether they are indeed marking their insistent presence.

In “Theorizing Queer Temporalities” (2007), Carolyn Dinshaw put forward the idea of the existence of affective communities across time, as well as the coexistence of multiple temporalities in the present. Dinshaw considers ghosts as the ontological status of bodies that are not here and now anymore, but whose existence is prolonged by affective connections. I find this concept is useful because, if military violence in Chile used the extermination of physical bodies to extinguish an economic, social, and cultural project, the idea of an ontology of ghosts or hauntology works to explain the affective persistence of those bodies, and of that project. At the same time, Carla Freccero points to queer spectrality “as a phantasmatic relation to historicity that could account for the affective force of the past in the present, of a desire issuing from another time and placing a demand on the present in the form of an ethical imperative” (184). Freccero also notes that the body is conceptualized in Western thought as contained in a linear teleological narrative and a binary logic of presence/absence, and argues for an understanding of the presence of the past in the present in the form of a haunting, of the “cohabitation of ghostly past and present.” Building on this notion of the affective force of the past as an ethical imperative in the present, we can rethink how a diversity of strategies that aim at bringing those bodies to the present—as ghostly presences—can represent not only the mourning of their disappearance, but rather, mark the affective persistence of a utopian project of social justice as a disruption to the oppressive present.

In Chile, the Red Chilena Contra la Violencia Doméstica y Sexual has carried out the campaign Cuidado! El Machismo Mata (“Warning! Machismo Kills”) since 2007, which puts forward a politicized reading of violence against women that links individual cases of violence to dominant narratives, practices, and cultural norms.

The public installations of this campaign have deliberately tried to establish associations between the killing and disappearance of bodies under Pinochet’s military dictatorship—deemed politically motivated—and male misogynist violence against women—deemed private, or domestic, thus “nonpolitical.” Invoking a tradition of making the bodies of the disappeared reappear through pictures and cut-out cardboard silhouettes, or actions such as the installation of women’s shoes or dresses with tags identifying the victim’s name and age, this campaign marks the ghostly persistence of these murdered women and calls audiences to be witness of the public dimension of this violence. The display of shapes of women’s bodies, pictures, and the project of a “memorial” of women who were victims of male violence, are all part of a strategy to situate violence against women within the discursive context of human rights, to politicize violence against women, and to point to the connections between male violence, gendered cultural norms of self-sacrificing mothers, and violent masculinities that were mobilized (but not invented) by the dictatorship. Cuidado! El Machismo Mata seems highly effective in making such connections between the “public” and the “private,” and has raised the visibility of violence against women by introducing a more complex analysis that shifts the focus from individual personalities, pathologies, and predispositions, to bring it to the realm of state practices, nationalist ideologies, and gender norms.

The public installations of this campaign have deliberately tried to establish associations between the killing and disappearance of bodies under Pinochet’s military dictatorship—deemed politically motivated—and male misogynist violence against women—deemed private, or domestic, thus “nonpolitical.” Invoking a tradition of making the bodies of the disappeared reappear through pictures and cut-out cardboard silhouettes, or actions such as the installation of women’s shoes or dresses with tags identifying the victim’s name and age, this campaign marks the ghostly persistence of these murdered women and calls audiences to be witness of the public dimension of this violence. The display of shapes of women’s bodies, pictures, and the project of a “memorial” of women who were victims of male violence, are all part of a strategy to situate violence against women within the discursive context of human rights, to politicize violence against women, and to point to the connections between male violence, gendered cultural norms of self-sacrificing mothers, and violent masculinities that were mobilized (but not invented) by the dictatorship. Cuidado! El Machismo Mata seems highly effective in making such connections between the “public” and the “private,” and has raised the visibility of violence against women by introducing a more complex analysis that shifts the focus from individual personalities, pathologies, and predispositions, to bring it to the realm of state practices, nationalist ideologies, and gender norms.

In Canada, the collaborative project Walking with Our Sisters, initiated by Metis artist Christie Belcourt, features an installation that commemorates the lives of the missing and murdered Indigenous women and of victims of residential school by displaying 1,800 vamps, the decorative tops of moccasins, laid out in a way that takes audiences/participants down a winding pathway. The locations where the installation has toured are mostly art galleries and universities. The process of putting together the installation is significant, as it was a collaborative effort of hundreds of individuals who decorated the tops with beads. The practice of beading is in itself an exercise of putting love and care in every stitch as mindfulness connectedness with others that are not here anymore. The audiences remove their shoes and walk by the unfinished moccasins which are to represent the women’s unfinished lives, following traditional protocols such as smudging and pipe ceremonies indicated by elders. Belcourt actually describes the exhibit as a ceremonial memorial based on Indigenous knowledge and explains that to properly honor the women, we cannot limit to words and pictures but we need the ceremonial aspect to address the value of their lives. The memorial also acknowledges all the women that have been murdered from colonial violence for hundreds of years, not just these last decades.

The audiences participating in the ceremony cannot stay disconnected as mere spectators, neutral observers, but are rather interpellated and transformed. I consider this form of installation as performance as it puts forward the obstinate presence of the bodies of the murdered and disappeared women in a semi-public space. In a similar vein, the REDress project, created by Metis artist Jaimie Black, follows a similar strategy of installing donated red dresses in public spaces that both interpellate audiences about colonial violence against Indigenous women and bring the absent bodies back by marking their ghostly persistence. I see connections between these forms of “public grieving” as they both function like social communal performances that interpellate audiences about our accountability and responsibilities to each other, both in contexts of “reconciliation”. In both contexts, this reconciliation processes are state-led, and have produced TRC reports and forms of memorialization that put violence and trauma as a thing of the past, which thus needs to be overcome. These performances stubbornly assert the existence of bodies that are not present, and refuses the binary of private and public, which only serves to make invisible the connections between our individual and subjective experiences with larger structures and systems.

The audiences participating in the ceremony cannot stay disconnected as mere spectators, neutral observers, but are rather interpellated and transformed. I consider this form of installation as performance as it puts forward the obstinate presence of the bodies of the murdered and disappeared women in a semi-public space. In a similar vein, the REDress project, created by Metis artist Jaimie Black, follows a similar strategy of installing donated red dresses in public spaces that both interpellate audiences about colonial violence against Indigenous women and bring the absent bodies back by marking their ghostly persistence. I see connections between these forms of “public grieving” as they both function like social communal performances that interpellate audiences about our accountability and responsibilities to each other, both in contexts of “reconciliation”. In both contexts, this reconciliation processes are state-led, and have produced TRC reports and forms of memorialization that put violence and trauma as a thing of the past, which thus needs to be overcome. These performances stubbornly assert the existence of bodies that are not present, and refuses the binary of private and public, which only serves to make invisible the connections between our individual and subjective experiences with larger structures and systems.

Trauma, performance, and the body

If memory is the work of introducing a narrative, or imposing sense and meaning to experience, performance can be understood as what Nelly Richard calls "the conflict of narrating what cannot be narrated," especially when we try to use language to communicate experiences such as torture, dispossession, or the loss of language, which in itself involves the loss of a sense of identity. Transitional politics in Chile have managed to subordinate the practices of memory to their official representation in state produced reports and to its monumentalization in memorials that relegate state violence as something that happened in a faraway past, as opposed to something that continues to happen (state colonialism, poverty, discrimination, police repression, the denial of justice, etc.). While formal political practice in Chile has been constrained by the dominant narratives of reconciliation and of “democracy within the measure of the possible,” street performance has been politically effective, not so much in terms of offering a convincing rhetoric or agenda for emancipation, but as far as outlining the existence of other subjectivities, as well as being able to "change the cartography of the perceptible, the thinkable and the feasible" (Ranciere, 72). Activist and protest performances seem effective as they can generate multiple and scattered “scenes of dissensus” that can open up new forms of political subjectivation. Moreover, since there is always some portion of the bodily experience that resists signification—a surplus, an excess—performance allows these sites of excess, points of discursive failure, and non-sense of experience to be used as points of entry for articulating political subjectivities outside formal politics.

As Coco Fusco has argued (2000), the body, the very material for activist performance, it is also the material and concrete site where political power has been (violently) articulated, within the particular historical coordinates of colonial genocide, imperialism, and globalized capitalism in the Americas. So if the body is the material site where political regimes are articulated, then Fusco sees performance practices as able to deconstruct particular versions of the body in order to address the violence of the discourses that constitute them. Actions such as flashmobs and round dances offer alternative forms of embodiments of subjectivities, political projects, and political imaginations, based on the “interconnection of bodies,” rather than on their individual rights and bodily sovereignty.

The Chilean secondary student’s movement erupted during Michelle Bachelet’s first government (2006), emerging as a political and social movement whose claims for a free, universal, quality education system fell completely outside of the measured agendas of the governing Concertación center-left coalition. The use of performance as protest deployed within the student’s movement had the ability to both intervene in the present while changing or keeping dynamic the readings of the past. Making the “past” (the project of socialism) a utopian project again, the past becomes the future (is not necessarily “behind” it). The students’ movement has managed, since then, to completely change the collective imaginaries of what is possible. The student movement embodied a new generation that disrupted the illusions of continuity of reconciliation and national unity of the post-dictatorship. As part of the varied and creative range of the student movements’ protesting tactics, take for example their flash mob of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” in June of 2011. They interrupted and stopped the regular circulation in public spaces, occupied them with their bodies to express a political message in a pleasurable, collective way (coordinated dance), and suffered, in their bodies, the repression that came as a consequence. We should not dismiss the significance of the spectacle of 4,000 adolescents pretending to be raising from their graves across La Moneda to demand free public education: It is not only as if the dead and the disappeared were rising from their (non-existent) graves, but also they were bringing back the project of public education and consciously opposing the main core premise of neoliberal ideology, profit (“el lucro”), since the students were protesting the educational model installed under Pinochet’s rule that made it possible to profit with public education.

The Chilean secondary student’s movement erupted during Michelle Bachelet’s first government (2006), emerging as a political and social movement whose claims for a free, universal, quality education system fell completely outside of the measured agendas of the governing Concertación center-left coalition. The use of performance as protest deployed within the student’s movement had the ability to both intervene in the present while changing or keeping dynamic the readings of the past. Making the “past” (the project of socialism) a utopian project again, the past becomes the future (is not necessarily “behind” it). The students’ movement has managed, since then, to completely change the collective imaginaries of what is possible. The student movement embodied a new generation that disrupted the illusions of continuity of reconciliation and national unity of the post-dictatorship. As part of the varied and creative range of the student movements’ protesting tactics, take for example their flash mob of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” in June of 2011. They interrupted and stopped the regular circulation in public spaces, occupied them with their bodies to express a political message in a pleasurable, collective way (coordinated dance), and suffered, in their bodies, the repression that came as a consequence. We should not dismiss the significance of the spectacle of 4,000 adolescents pretending to be raising from their graves across La Moneda to demand free public education: It is not only as if the dead and the disappeared were rising from their (non-existent) graves, but also they were bringing back the project of public education and consciously opposing the main core premise of neoliberal ideology, profit (“el lucro”), since the students were protesting the educational model installed under Pinochet’s rule that made it possible to profit with public education.

Additionally, performance can also work as communal rite of healing, such as the dance troupe Butterflies in Spirit from Vancouver, in the unceded Territory of the Coast Salish. This troupe is formed by family members of the MMIW but does not follow traditional protocol: the dancers will perform choreographed dances to the music of Beyonce and end up performing the Warrior Sing. They bring their dance to interrupt the oppressive normal flow of cars, capital, and business in downtown Vancouver, and tell the story of the missing and murdered women with their bodies, while using dance and movement to heal from the trauma of colonial violence. Perhaps the function as a rite of healing and coming together is even more poignant in the flashmobs carried in the context of INM activism, which is based on establishing alliances between Indigenous and non-Indigenous allies to challenge ongoing colonialism. By pointing at the continuity of collective bodies, the performance of flash mobs and round dances challenge where one body begins and another ends. Despite the narrative of the self-sufficient body, humans have no chance of developing subjectivity or even of physically surviving without connection to others. Our bodies are also connected by eyes, mouths, and hands, sometimes through remote devices, sometimes through touch, speech, sight, etc. While the modern Western idea of the body defines it as a realm of the private and the individual, the performances I have discussed make evident the public dimension of bodies, and in Jose E. Muñoz’s words, “allow us to see our numbers and our masses.” They point at the limits of traditional political practice at imagining alternatives, as well as to the impossibility of language in conveying trauma in contexts of state terror and colonial violence.

Looking at the use of performance tactics for activism across America/Abya Yala, illuminates the ways that social movements and activists are challenging deeply embedded ideas about temporality, and about the gendered division between public and private space, as they mark the presence of utopian projects and subjects. I hope that these thoughts can raise some questions and trigger further conversation between activist and scholars that can contribute to decolonizing our imaginations and building anti-capitalist and anti-colonial solidarity across our continent.

Looking at the use of performance tactics for activism across America/Abya Yala, illuminates the ways that social movements and activists are challenging deeply embedded ideas about temporality, and about the gendered division between public and private space, as they mark the presence of utopian projects and subjects. I hope that these thoughts can raise some questions and trigger further conversation between activist and scholars that can contribute to decolonizing our imaginations and building anti-capitalist and anti-colonial solidarity across our continent.

Comments

Post a Comment